Last updated: 07 Nov 2022

7 mins readIt’s been (almost) two years since I started my first steps in the Rust world. I thought it could be interesting to reflect on some impressions and lessons learned during this journey.

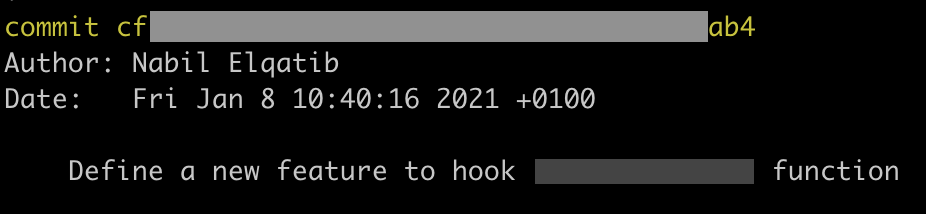

Below is my first commit in a Rust repository. Although it dates to Jan. 2021, I have been fiddling with it (cf. the title of this article!) for several weeks.

How did I get into Rust in the first place?

I had long heard about Rust before landing a new job in December 2020. Coming from the embedded world, my view of Rust was that of a modern and powerful language that could eventually be a legitimate successor to C/C++. Somewhere inside me was an apprehension that I could be missing the start of a new era.

Spoiler: As it turns out, Rust did not replace C/C++, but it’s steadily gaining momentum. It benefits from growing popularity amongst developers1, and even Google is looking at it with great interest23.

Impressions

First, a quick caveat. It should be stated that I did not have any formal learning of Rust. Instead I only learned by doing, reading code and sifting back and forth through documentation. In retrospect, I don’t think this is good practice, and I strongly believe spending some time to leverage a quick understanding of the language, its philosophy, and its ecosystem using the official learning material is a must before getting into serious things heads down.

Rust learning curve is steep

Rust, as I remember, was “sold” to me as a strongly-typed language with the promise of great tooling to prevent memory-safety bugs (see the following section) by tracking object lifetime and variable scope of all references during compilation. Enters the borrow-checker!

What seemed like a quite simple idea (the Rust documentation on this part is really comprehensive)

turned out to be a nightmare at times when working on multiple crates with statics and Rcs,

and other subtle language artifacts.

At the time, I had a hard time wrapping my head around this new concept, and the easy loophole

was constantly cloning variables around which is not only bad, especially when dealing with large

data structures, but also had the side effect of pushing back the moment when I finally got a good grasp of it.

Fortunately enough, the compiler comes to the rescue with very helpful hints and pointers to the documentation, which I must say are really helpful.

Compiler is not a formal verification tool

This is a very common misconception that stemmed from a recent conversation with one of my non-Rust engineer colleagues. For him, it was inconceivable that a Rust program would panic because of an out-of-bounds runtime memory fail. Unfortunately, the Rust compiler is not a one cure for all diseases, and obviously it is easy to trick it into successfully compiling a program that only fails on runtime. Take the following example that uses a very common Rust data structure:

let mut v = vec![];

v.push(0);

v.clear();

let _ = v[0]; // panics

Or even trickier:

let mut v = Vec::new();

#[cfg(target_os = "windows")]

v.push("a");

let _ = v[0]; // panics

Detecting an out-of-bounds access at compile time requires a deeper analysis of the code that would significantly slow down compilation time (which is already too slow IMO).

Rust can be unpredictable

This section is about a recent behavior I observed where our team woke up to one of our

crates’ (dependencies’) dependencies starting to panic in production under specific conditions.

Long story short, a specific version of reqwest

raises an error and panics if a system certificate is bad when used with the rustls-tls-native-roots feature.

This came as a surprise to me because it makes dealing with dependencies somewhat risky.

Eventhough most crates are nowadays open source, one can reasonably not audit all their source

code to assess the “risk” of using them. The poor documentation of most crates also supports this point.

Having a cargo tree-like tool that analyzes a project’s

dependencies and gives a bird’s-eye view of the crates that are panic-prone would be very helpful.

A quick idiomatic alternative to dealing with this problem could be overriding Rust’s

panic_handler but unfortunately this is only possible in #![no_std] projects.

Program binaries can be huge

Speaking of no_std… coming from the embedded world, this is a particular point of interest to me.

I haven’t had (yet!) the opportunity to write Rust code for memory-constrained/low-end devices

and peripherals. Although this is not an immediate concern to me today, Rust binaries come with a

non-trivial size overhead.

I’ve read several blog posts and papers on this topic, in partiuclar, Jon Gjengset’s videos are

of great interest as they give a real hands-on overview of it. But my point here is that Rust still

has a long way before becoming a serious contender to C for memory-limited targets.

In the #![no_std] world, I believe Rust still needs to figure out a way to provide viable panic

handler libraries that don’t rely on out-of-the-box formatting functions as these can be

very memory-consuming,

this article by James Munns was a real eye-opener to me.

Rust tooling is great for interoperability

Now this is also something that positively struck me.

One of the projects I worked on consisted of bridging 900K+ lines of C code from and into Rust. There was no great difficulty in doing this, because Rust makes it really easy, and this use case seems to be pretty well established as there are many crates and examples out there. Writing Rust bindings for foreign code is made relatively straightforward through the FFI machinery, I can’t speak for all the languages but languages belonging to the C-family (C/C++/Objective-C) are well supported.

This doesn’t mean there is not much work to do, as you still need to have some “plumbing” code here and there to glue things together, but it’s the price to pay and I think it’s fairly low. Also, it’s nice to see Rust sticking to its philosophy and requiring shady low-level code to be declared unsafe (basically all FFI functions are de facto unsafe because Rust can’t have any control on the arbitrary code written in another language.)

Rust is powerful

Still, I would like to end this blog post on a positive note. Rust is a really rich language allowing for potentially great advances in systems programming. Strict ownership and borrowing help to ensure that data are accessed safely and efficiently. Its modern syntax and design allow for an easier understanding and usage of programming languages software patterns and recent paradigms. Also, it is not so much spoken about, but Rust does a really good job making sure threads run concurrently without race conditions and similar issues.

A word to end

I really enjoyed working with Rust. If I had the choice of a new software development language to learn in 2020 or even today in 2022 I’ll definitely choose it, no hestitation. I see in it so much potential and hope it’ll gain more visibility in the embedded systems world in the upcoming months. The recent introduction of a Rust Linux kernel module shows great promise and a bright future ahead.

On a more personal note, I wish to be more involved in shaping Rust’s future by making contributions to its software while keeping learning its concepts and intricacies.

External references

-

For the seventh year in a row, Rust topped Stackoverflow’s 2022 survey as the most loved programming language. ↩

-

Android next-gen BLE stack is being written in Rust: https://www.reddit.com/r/rust/comments/mgz7y5/androids_new_bluetooth_stack_rewrite_gabeldorsh/ ↩

-

KataOS, Google’s new secure OS is also implemented almost entirely in Rust: https://opensource.googleblog.com/2022/10/announcing-kataos-and-sparrow.html ↩