5 mins read

I have recently completed my first project working independently for a client. The joy of securing a contract in today’s job market was so high that I made a few mistakes along the way — from kicking off the project to delivering what the client requested.

For the record, my client was an interior design company working on the new design of a coffee shop located in a very famous Parisian upmarket department store chain. They wanted a video system that would play looping videos (the easy part) and automatically switch to a live camera feed whenever the barista started pouring milk foam into a customer’s cup, to enhance the experience.

My client, who didn’t have a technical background, submitted their request with a prior research on the topic. They had already used ChatGPT to gather information on hardware selection and cost estimates. We quickly agreed on the most important elements: it would be a Raspberry PI 4-based system, with a “good enough” RPI camera and lens.

This was the first mistake.

Lesson 1: Don’t let a non-experienced client influence technical choices you’re ultimately responsible for

When you don’t have a product manager as an interlocutor, it’s up to you to do the non-technical work: defining specifications, tasks, and more importantly, making technical choices.

Spend enough time and effort to thoroughly understand the project, its environment, and the exact use case to address. Talk with your client, and suggest better or alternative approaches based on your experience, to work around difficult or unrealistic demands.

You’re responsible for the technical choices as long as they fulfill the requirements. This also goes hand in hand with cost and availability.

This was the second mistake.

Lesson 2: Quote your work separately from hardware costs

Unless you specifically offer hardware sourcing as part of your services, it’s usually a good idea

to let the client handle the purchases. This keeps your responsibilities clear and protects you from

unexpected delays due to stock issues or last-minute spec changes. Hardware parts can sometimes be

tricky to source, or to receive within reasonable timeframes.

More importantly, when hardware

costs are bundled into your quote, your actual profit can shrink if the client changes their mind or

requests better parts, leading you to absorb the difference. Your role is to provide guidance and

expertise; keep the hardware costs separate so that your compensation reflects your work, not

fluctuating material prices.

In my case for example, the client requested hardware purchases I was pretty sure were unnecessary. For example, we used a 1m flex cable from Adafruit, but the client insisted we also purchase the 2m model, just in case the final RPI’s location was farther away from the camera (which eventually turned out not to be the case.)

It’s not about being extra stingy, but sometimes there’s no point purchasing exotic parts that will end up sitting unused on your shelf.

There is another mistake.

Lesson 3: Always have spare parts ready for replacement in case anything doesn’t go as expected

Anything that can go wrong will go wrong — so be prepared for it.

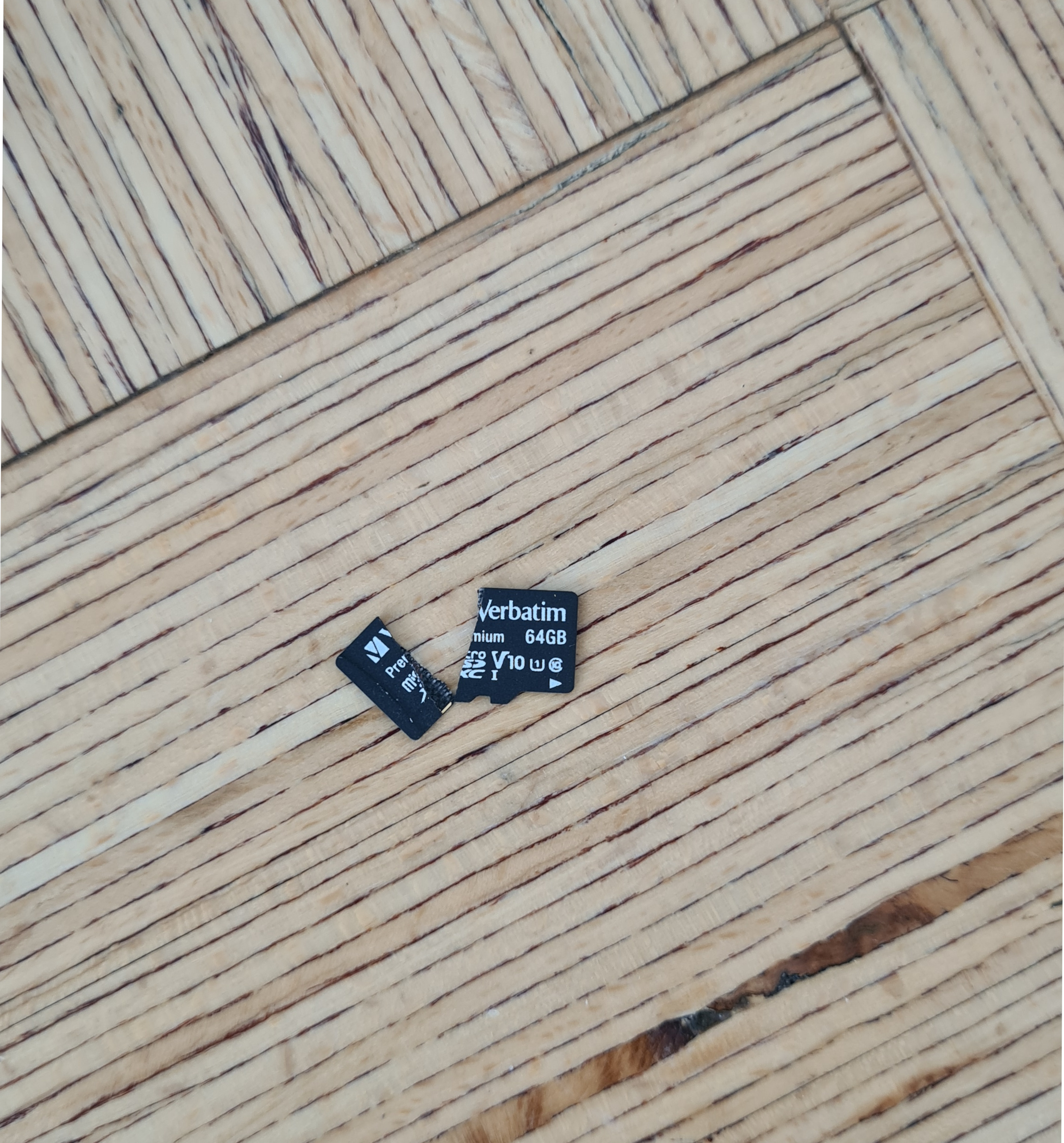

The final day was incredibly stressful. It was D-minus 1, and everyone was on site finishing their work: plumbers, electricians, painters, you name it. While mounting the Raspberry Pi into its aluminum case, I didn’t pay enough attention to its orientation and accidentally damaged the microSD card. The OS failed to boot, and after a few attempts, the card became completely unusable, eventually tearing apart in the process.

Luckily, I had documented a fresh install procedure with all the required configurations and software and brought my microSD-to-USB adapter just in case I needed to reflash the OS. What I didn’t have was a spare microSD card. So, I quickly grabbed a Velib’ electric bike and dashed to the nearest electronics store under the sweltering Parisian June sun.

But the story doesn’t end there. My microSD adapter decided that was the perfect moment to start acting up. Despite going to great lengths to get it working reliably, it was flaky. This was a serious blow to morale. And then (completely unexpectedly!) someone onsite had a spare microSD adapter. It was only a matter of installing Raspberry PI imager and waiting for the OS to be flashed, and it worked. I was lucky this time, but I don’t intend to rely on luck again.

Lesson 4: Agree on a deadline for implementing new features

Among other things, good software engineers care deeply about code quality. They spend a considerable amount of time testing software. In particular, they despise last-minute feature requests as they fear they cannot be tested thoroughly (especially in a short-lived project with no automatic test infrastructure).

Being present onsite for the final setup meant meeting with different people who saw a demo of the system for the first time. And almost each one of them had their own opinion and feature ideas for improvements. But it was too late, and I was very uneasy in refusing or dodging their requests.

Final thought

Making mistakes early in your career is normal. Don’t be hard on yourself. Learning from them is

invaluable to sharpen your skills.

To make that learning process more effective, you can adopt post-mortems as a regular practice after

every project you work on, even when it’s not a failure. It’s a great way to highlight your

shortcomings and proactively find ways to avoid them.